Explorations

A Lexicon of Media Concepts

The texts collected in The Promise of Cinema are strewn with sparks of insight relevant to audiovisual media and media imaginaries beyond their immediate context. While these sometimes stand front and center in the text, they are often more elusive, couched in a fleeting sentence or even an aside that can easily be overlooked. This section draws on the Internet to bring observations and ideas from the texts to life. Mixing image, text and sound, these Denkbilder could be compared to audiovisual emblems or video aphorisms (rather than video essays). While a few of the connections here are illustrative, showing films a writer was referring to or films that she or he might have seen, most are more creative, probing the potential afterlives of ideas and concepts from the texts. We welcome contributions from readers.

Archive

In the film archives of a single German film company, Ufa for example, there are hundreds of thousands of meters of unused film material. They are images of life, documents of human existence, of animals, plants, documentary images of landscapes, buildings and cities, and objects of every kind; images of the conventions and customs of people from every nation, of natural disasters, accidents, work processes, of everyday events, not staged, but rather shown as this everyday life appears before the cameraman’s lens. Filmic documents that encompass the entire life of contemporary people. This indescribable wealth of raw material for Kulturfilms remains largely untapped.

Albrecht Viktor Blum, Documentary and Artistic Film (1929), no. 45

Albrecht Viktor Blum, The Shadow of the Machine (1928)

Bodies

How often we used to express the wish, in earnest or jest, that the doctor could see inside his ill patient—and now he can do just that! The unimaginable has come to pass.

Anonymous, “Cinema in the Light of Medicine” (1913), text no. 236

Dr. Mackintyre’s X-Ray Films (ca. 1908)

Live cell imaging using far-red DNA stain and superresolution microscopy

Consciousness

This is the new, objectified form of human consciousness. As long as these men do not lose consciousness, their hands will not loosen from the grip of the camera. Shackleton’s ship is wrecked by the masses of ice. It is filmed. Their last dog drops dead. It is filmed. The way back to life is blocked; all hope is gone. It is filmed. They drift at sea on an ice floe, which melts underneath their feet. It is filmed. Or Captain Scott pitches his last tent and goes inside with his comrades, as if into a tomb, to await death. It is filmed. Just as the captain on the ship’s bridge and the telegrapher in front of the Marconi instrument continue in their posts until the water reaches mouth-level, so too does the operator stay at his post and film until his hand freezes on the camera’s grip. This is a new form of self-reflection. These people reflect themselves by filming themselves. The inner process of accounting for oneself has been externalized. This self-perception until the final moment is mechanically fixed. The film of self-control, which consciousness used to run within the brain, is now transposed onto the reel of a camera, and consciousness, which has mirrored itself for itself alone in internal division until now, delegates this function to a machine that records the mirror image for others to see as well. In this way, subjective consciousness becomes social consciousness.

Bela Balázs, “Reel Consciousness” (1925), text no. 23

Shackleton

Disappearance

Not only is the modern battlefield so spread out that no cinematic camera could ever survey it completely, but it also has the principal characteristic of offering nothing, or at most very little,‘to see.’

Hermann Häfker, “The Tasks of Cinematography in this War” (1914), text no. 113

Messter-Woche no. 9 (1915)

Iraqi air defense (1993)

Dream

The trueness-to-life of the cinema is in no way bound or tied to our reality. Furniture moves around in the room of a drunkard. His bed flies with him high over the city—in the very last minute he is able to hold firmly onto the bed rail and his nightshirt waves around him like a flag.

Georg Lukács, “Thoughts on an Aesthetics of Cinema” (1911/13), text no. 174

Edwin S. Porter, Dream of Rarebit Fiend (1906)

Christopher Nolan, Inception (2010), excerpt

Education

Germans have a marked predisposition for archives and museums. No other nation on earth has collected everything with such fervour and such scientific thoroughness, everything that is or could somehow be the object of scientific research. The essence of any archive, its true purpose, consists in wresting objects away from their fate of impermanence, since they would otherwise be doomed to loss and decay, would get swallowed up and worn away in the stream of time. The true purpose of any archive consists in conserving objects and putting them in order, thereby making it possible to group them together or apart from one another by means of comparison.

Fritz Schimmer, “On the Question of a National Film Archive” (1926), no. 44

Max Reichmann, Das Blumenwunder (1926)

Environment

Now the “sprayman” goes to work. From a large bottle, he sprays “ozone” (as they mockingly call this movie theater perfume) over the heads of the audience gasping for breath. Under this watery mist, the atmosphere in the cinema, already lacking in air, grows even more stifling. All of the audience members breathe as if asthmatic; nevertheless, they endure it. They would rather risk a temporary loss of consciousness than miss the show they’ve paid for (just as one does not wish to forego a drink one has bought in a bar).

Viktor Noack, The Cinema: Thoughts on its Nature and Significance (1913), text no. 67

BBC report on wifi radiation (2011)

Event

Systematically implemented recordings of the current state of our public squares, our games, our social systems, our transportation would provide material of practically infinite value for the generation that, by the year 2000, will rule not only the earth, but probably the skies as well. Would it not be wonderful if that generation had a successful picture of the historical moment when Count Zeppelin completed his grand journey and, for a moment, had to admit defeat in the struggle against nature?

Ludwig Brauner, “Cinematographic Archives” (1908), text no. 38

{'img': '', 'alt': 'Film the Zeppelin (1908)'}

Filming the Zeppelin on Lake Constance (1908)

Maiden Flight of the Zeppelin (1908)

Futurology

[Submitted by Nathaniel LaCelle-Peterson]

For the present time – more than any other time – demands foresight. The present is determined by tomorrow, not yesterday. No history can help us to comprehend film; we need, instead, utopia. Not the utopia of an erratic, directionless fantasy, but rather a bold and precise calculation based on the data of our existing strengths. It is astonishing, bizarre, absurd how backwards we remain in this very science. For utopia can be a science. What will be may be predicted with reference to existing facts, just like the movement of the celestial bodies for hundreds and thousands of years… What is decisive… [is] seeing future transformations to our world, transformations that follow from necessity and are determined by technology.

Frank Warschauer, “Glance into the Future” (1930), text. no. 274

Ray Kurzweil, “The Accelerating Power of Technology” (TED Talk)

Globalism

The international language of gestures defeats all national languages. Films of the Rhine can be enjoyed with equal understanding on the banks of the Bosporus, the Ganges, or the Nile. In this way, the cinema stormed across the globe, swift and victorious in battle. From the beginning, the film industry could say: The world is my domain.

Adolf Sellmann, “The Secret of the Cinema (1912), text no. 10

Walter Ruttmann, Melodie der Welt (1929)

Kevin MacDonald and Ridley Scott, Life in a Day (2011)

Immortality

The Kingdom of Death no longer provides the imminent frontier to life. Through these eyes, Leo XIII need not have ceased to project his benevolent smile, to pray for us and bless us with his papal grace. The Kingdom of Death stops at the border of the cinematograph and the gramophone.

Gustav Melcher, “On Living Photography and the Film Drama” (1909), text no. 3

Pope Leo XIII, oldest footage of a pope

Audiences will take delight in the performance without considering the efforts and costs of the recording of such “singing pictures.” The latter are quite interesting, but they have a melancholy air when they include artists who have died, and whom we believe to see and hear, brought back to life before us.

Anonymous, “How Singing Picture (Sound Pictures) are Made” (1908), text no. 247

Rauschlied von Künstlerblut, Tonbild with Alexander Girardi (1908)

Michael Jackson performing via hologram at the 2014 Billboard Music Awards

Matter

Film—“preserved time” as it were—shares the same fate as life: it too perishes; its basic materials, appearing in space, change quickly, and with them, so does the breath of life that was cast over it like a spell and that may seem to create the illusion of a temporal event again through a wonderful mechanism in the light of the projection lamp.

Fritz Schimmer, “On the Question of a National Film Archive” (1926)

Jürgen Reble, Instabile Materie (1995)

Memory

Memory has ceased to be dependent upon that off-white and fickle mass we call the brain. The modern man does not remember. He collects and uses “cinegrams.” Clio, the Muse of History, has ceased to write shorthand or type events into the Book of History. Clio turns the crank of the cinematograph and operates the phonograph.

Gustav Melcher, “On Living Photography and the Film Drama” (1909), text no. 3

Chris Marker & Yannick Bellon, Rememberance of Things to Come (excerpt, 2003)

Let us imagine that the cinematograph, rather than being a little over ten years old, were over a hundred, and we could see films that had been preserved from the so-called good old days. What a clear picture these untouched, truthful documents could offer us of times gone by! A single filmstrip could show us more than two dozen books created by arduous research and tedious study. Consider a simple street scene. What information could it offer about life and goings-on in a small city back then? It would not only show us clothing and shoes, but people’s gait, social systems, types of movement in the street, traffic, in short everything that we currently have to imagine based on paintings, engravings, and descriptions that have been handed down to us. A single filmstrip would give us information about a thousand little things that we no longer know and which therefore seem unfamiliar and strange.

Ludwig Brauner, “Cinematographic Archives” (1908), text no. 31

Studio Guido Seeber, Molkerei Franz Lange (1920)

Motion

The naturalist, the explorer, and the biologist will find an indispensable tool in the cinematograph whenever they wish to bring back evidence, as we may call it, from their travels—evidence of what they saw and observed in terms of customs and habits of people and animals that might someday disappear.

Osvaldo Polimanti, The Cinematograph in Biology and Medical Science (1911), text no. 234

Qualisys motion capture of horse and rider

Museum

There are libraries and art galleries. There are museums of art history and of general cultural history. There are special collections and archives for everything. The slightest product of human creativity becomes a document of development through the sheer fact that things were once different, and thereby gains historical distinction. It is the first sign of a guild or trade’s self-regard when it commemorates its own history. History is the spiritual area for beginning to advance into the future. Cobblers, tailors, and brush-makers find the works of their ancestors in special museums. In technical museums, one can trace the development of the lavatory. Yet there is no museum for film art.

Béla Balázs, “Where is the German Sound Film Archive?” (1931), text no. 46

Pictures at an Exhibition (Chris Marker, 2008)

Nervousness

After hardly more than five hours, the subject grew extremely weary, his eyelids became heavy, and he explained: “I can’t go on. I can’t take it anymore. My head is spinning and my eyes hurt.”

Nado Felke, “Cinema’s Damaging Effects on the Health” (1913), text no. 99

Logo of Der Kinematograph (1915)

Obsolescence

Many films from that bygone era are now simply comical. Not in the places where they try to be comical but rather, precisely at the heights of seriousness. In the middle of a graveyard scene, for example, which apparently forms the poignant conclusion to a dramatic plot, we find the kneeling Henny Porten alongside a well-dressed gentleman who would be at home in any Courths-Mahler novel. The commentary accompanying the image tells us: “No place on earth would I sooner crave / But here beside my family grave.” […] The comic effect issues from a certain transformation that has befallen these images. While they showed their original viewers only the content they intended, what they show viewers today is the peculiar and decaying milieu in which that content manifested itself as naïvely as if it were rooted there. We see not only the gentleman’s emotion but also his antiquated jacket, and we are forced to notice that Henny Porten’s sadness resides just beneath the outmoded shape of her hat.

Siegfried Kracauer, “On the Border of Yesterday” (1932), text no. 278

Still from Am Elterngrab, Messter Tonbild (1907)

Perception

. . . only film technology can produce a rapid enough sequence of images to correspond, remotely, to our own imaginative capacity and imitate its disjunctive rapidity. In part, the weariness that overcomes us before theatrical artworks results not from the noble strain of artistic enjoyment, but rather from our effort to adapt to the ponderous life on the stage with its feigned movements. In the cinema, where this effort is absent, one can abandon oneself much more freely to the illusion.

Lou Andreas-Salomé, “Cinema” (1912/13) – Text no. 13

Oskar Fischinger, Walking from Munich to Berlin (1927)

Remix

n order to produce meaningful representations of contemporary history in montage films created from this archival wealth, it would not even be necessary to have the hand of an artist […] The objects, in themselves and in their truth, already attain their full value as soon as a clean and sensitive hand arranges them in some sensible order. Of course, when doing this kind of work, one constantly risks becoming distracted by the abundance and charms of the material and turning away from the straight path to the specified goal.

Albrecht Viktor Blum, “Documentary and Artistic Film” (1929), text no. 45

Film ist, excerpt (Gustav Deutsch, 1998)

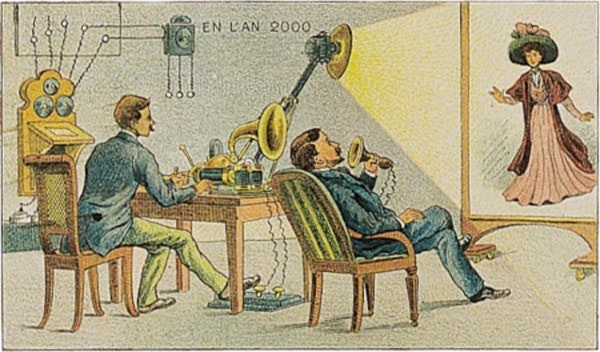

Telephony

In the future, perhaps our telephones will also have viewing openings or picture frames, where the person we are speaking with will appear. In business deals, for example, this will be a way for us to see prototypes or models from distant locations. We will also be able to see the faces of faraway family and friends. Of course, some people, like those who now hurry to the television in their pajamas when their sleep has been disturbed, will be upset by this invention, because they will have to get properly dressed with coat and tie in order to make a good impression.

Ernst Steffen, “Telecinema in the Home” (1929), text no. 273