Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

A Dancer on Film: Rudolf Laban’s Film Theory

KRISTINA KÖHLER

T he fact that film became an object of analysis at a time when dance, body culture and life reform movements were on the agenda has received comparatively little attention in film historical scholarship to date. Yet, especially in Germany, gymnastics and modern dance formed an important context that clearly resonated in the debates surrounding the new medium.[1] Not only were the same people—intellectuals, artists and critics—commenting on contemporary events in film and dance, but early film theory and modern dance were also surrounded by similar concerns and inquiries: When is a movement “beautiful”? What makes a body expressive? And which specific forms of a viewer’s aesthetic experience are addressed through movement?

Early film theoretical considerations had posed these questions with regard to concepts such as “expressive movement” and “movement arts” since the beginning of the 1910s. Authors like Herbert Tannenbaum and Béla Balázs referred quite explicitly to the dance and body culture of the time—for example, when it was appropriate to use dance as a model for silent but strongly expressive film acting.[2] By contrast, beginning in the 1920s, avant-garde theory appealed to the structural analogy of film as a “dance of images.” Filmmakers as distinct as Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, or Dziga Vertov and Germaine Dulac, composed a counter-cinema based on the model of dance and music, which sought to communicate not with story and words, but first and foremost with the interplay of sensual qualities like movement, light and color.

Excerpt from Studie Nr. 8 (D 1932, Oskar Fischinger)

We are currently restoring this media asset

By the same token, dancers, choreographers and dance theorists were among the artists and intellectuals who engaged with cinema at the beginning of the twentieth century. Their reactions to the new medium were deeply ambivalent—while modern dancers like Isadora Duncan and Mary Wigman spoke out decidedly against filmic recording of their dances, they were simultaneously fascinated by cinema as a popular entertainment medium. For instance, both Duncan and Wigman are said to have been passionate fans of cinema, eagerly going out to see the latest films and serials. Dancers’ commentaries—sometimes polemics against cinema, sometimes euphoric proposals for a transmedial movement art—open up a unique space for reflection on film. These comments show not only how closely dance and film cultures were intertwined, but also how they can be unterstood as early theories of body and movement in the cinema.

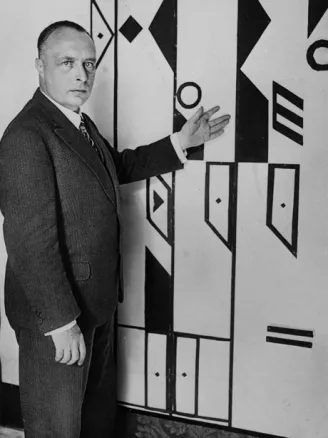

Among the dancers and dance theorists who were thinking about cinema at the turn of the twentieth century is the choreographer and dance theorist Rudolf Laban (1879-1958, born Rezső Laban de Vàraljas). As one of the leading figures of expressive dance, he joined the conversation in the late 1920s. He had spent the years between 1913 and 1919 researching “the natural motion of the human being” [“die natürliche Bewegtheit des Menschens”] in the artistic colony and life reform center on the Monte Verità.[3] After 1920, Laban shifted increasingly into theater and education: as a choreographer and artistic director at various German theaters and opera houses, he quickly came to oversee a comprehensive network of dance schools and held important positions in cultural policy. Laban’s contribution to the film theoretical debates in Germany in the 1910s and 1920s have received little attention to date, perhaps due to the difficulty of accessing sources. Most of Laban’s film projects are not available to us today (some were never made, others did not survive or have not been rediscovered yet). But the anthology The Promise of Cinema presents a document that allows us to look more closely at Laban’s thoughts on cinema—including their internal tensions and contradictions. Under the headline “Film and dance belong together,” Der Film-Kurier published a conversation between Rudolf von Laban and film critic Lotte Eisner.[4] This document from 1928 is remarkable for several reasons: it shows not only that dancers and choreographers like Laban were actively involved in the public debate on film, but also that concrete concepts of film as a “movement art” were being developed.

The article appeared in the summer of 1928, when public interest in expressive dance had reached its peak, in the context of the second German Dance Congress. A year earlier, dancers, choreographers, and dance critics had convened in Magdeburg for the first Dance Congress. The goal of the congress was to organize dance socially, politically and artistically, and to raise awareness among the broader public of the issues faced by dance and dance professionals.[5] Laban, who had participated in the organization of the Dance Congress, presented himself to the film critic Lotte Eisner as the spokesman of the modern dance movement. If Laban demonstrated a readiness to engage with the filmic medium, I argue that his primary aim was to emphasize the modernity of dance, and to situate dance as the key discipline for a modern world in movement. What is remarkable about Laban’s film theory is that is was not oriented towards the concept of a self-identical medium; he was much more interested in film as a heterogeneity of media practices, which allowed for diverse access points to the project of modern dance. This simultaneously allowed him a strategic opportunity to introduce his dance and film projects to the readers of the Film-Kurier.

In 1928, Rudolf von Laban presents his dance notation, “kinetography”.

I. Writing Dance. Film as a Tool for the Choreographer

The first matter that Laban highlights in his conversation with Eisner is the case for his dance notation system, on which he had been working since the 1910s and which he first introduced to a wider public at the Dance Congress in Essen. The name “kinetography” and the fact that he uses filmic terms like “roll” [Rolle] and “running strip” [laufendes Band] in his descriptions indicate the extent to which his conception—whether consciously or not—had been influenced by the model of film. Unlike previously existing notation systems, which remained limited to a specific dance vocabulary, this movement script—like film—was intended to suit any form of movement. Formally, Laban’s system was based on the five-line system of musical notation. These lines showed not only the rhythm and duration of a movement, but simultaneously marked spatial coordinates and signified a dancer’s individual body parts.[6] Furthermore, qualities of movement such as direction, impetus and force were also notated.

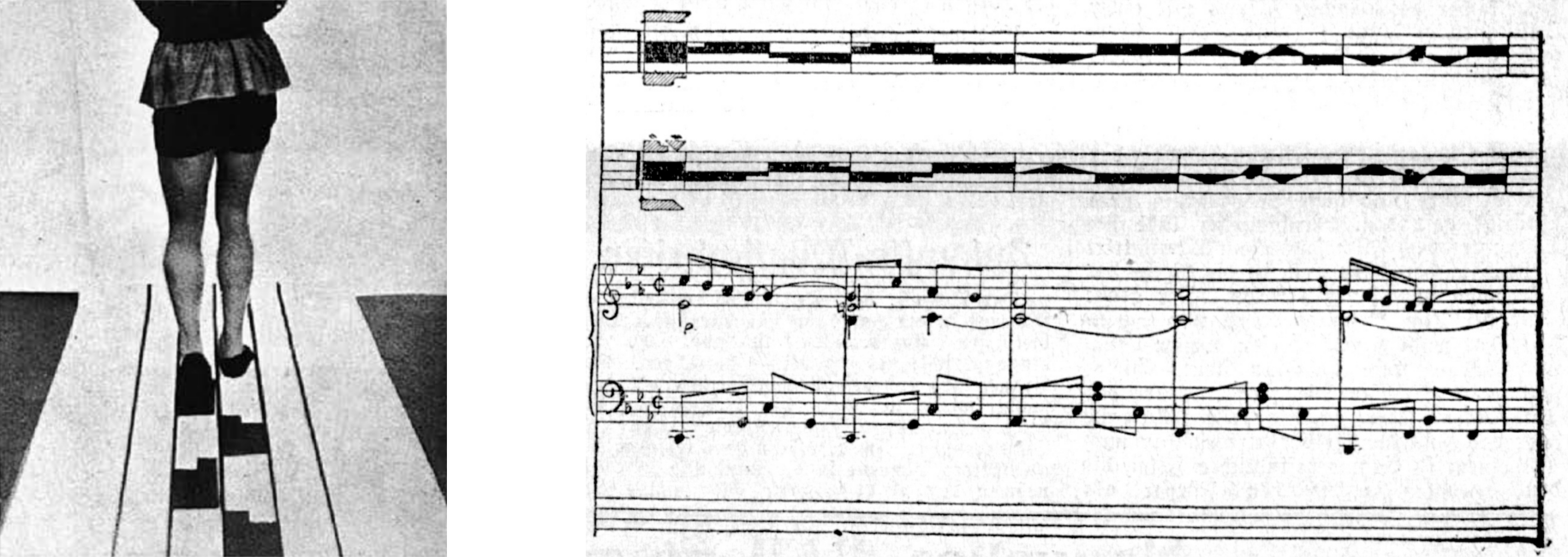

Laban’s “kinetography” is based on the five-line system of musical notation.

A crucial element was that Laban saw his “kinetography” not only as a tool for ex post facto illustration of choreography, but also as a creative and choreographic instrument, which would allow new dances to be fabricated in a written medium: “The goal is written dance, and by means of this written form of inscribed and thoroughly composed dance, the spiritualization—and with it, liberation—of the body: the wish and will of our time.”[7] With this function, namely as an instrument of planning and coordination, Laban also recommends his movement notation for use in film production. It would allow the director to “write down” a scene’s blocking before filming and to deliver it to actors “to study ahead of time.” The practice that Laban thus conceived is obviously connected to screenplay practices, but replaces dialogue with movement notation. The author Werner Schuftan made a similar argument in 1929. With Laban’s movement script, he wrote, a screenwriter could “clearly and unambiguously record in written form things that can only be expressed through motion, but never through words.”[8] Schuftan’s critique of the orally composed screenplay can be compared with voices that, starting in 1910, spoke out against the literarization of film and were therefore vehemently opposed to literary models and screenplays.[9] An interesting element of Laban’s and Schuftan’s position, however, is that they do not reject the screenplay, but rather take up script (movement notation) as a choreographic medium and present this as a counterexample to word culture. However, their suggestion resonated poorly in the world of film production; this may have been due, among other causes, to the large amount of time required to learn the notation system, which undermined Laban’s argument regarding “work simplification.” It is also questionable how much demand existed in the film sector for an instrument of movement planning.

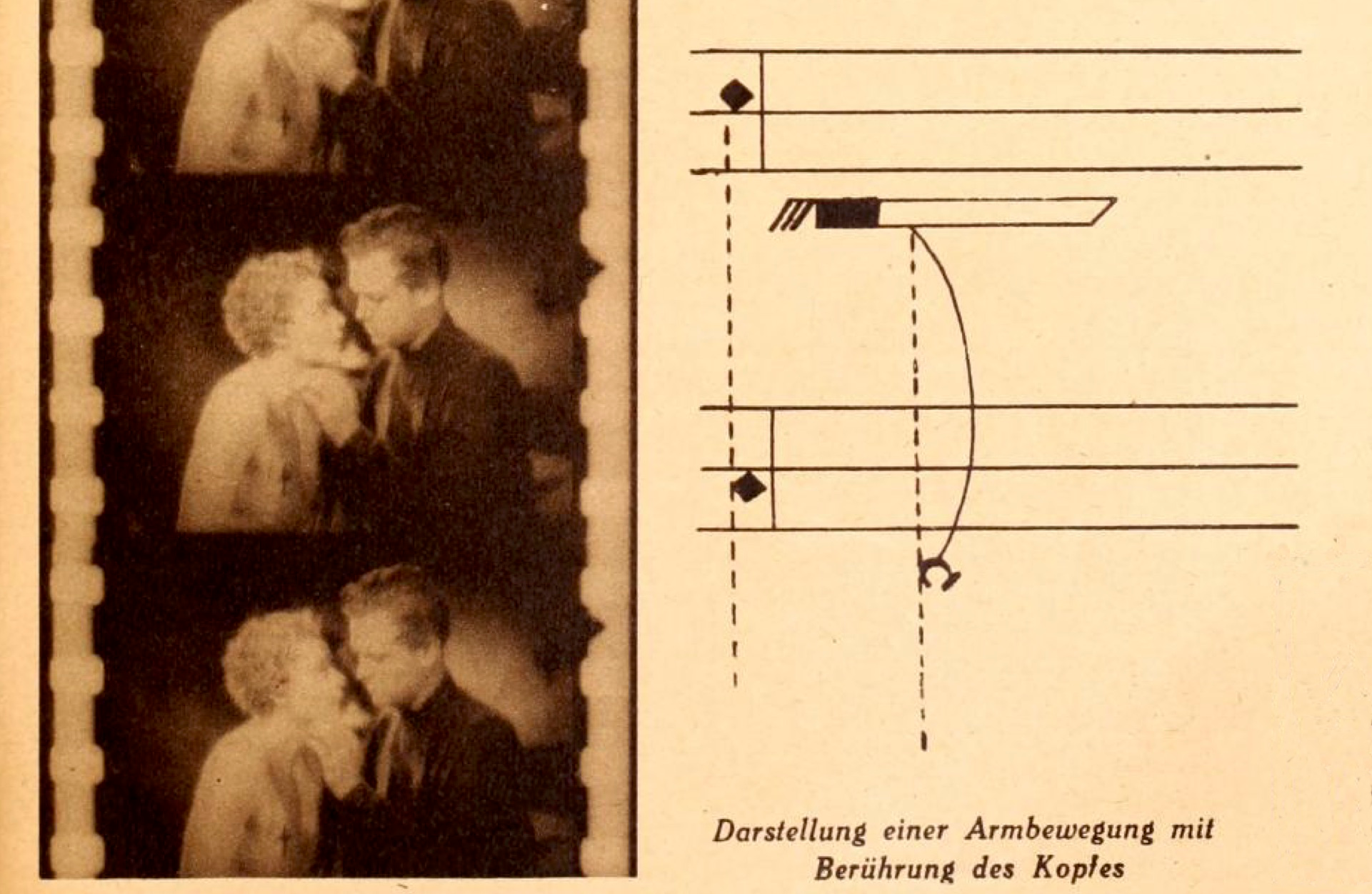

With Laban’s movement script, gestures and blocking for film scenes could be planned in advance, advises Werner Schuftan in 1929.

II. Mediating Dance. Der Kulturfilm as Tanzfilm – and the Education of the Masses

A second aspect that Laban emphasizes in the Film-Kurier is his own experience with film. This is significant because the use of film was quite controversial among dancers and choreographers of expressionistic dance. Depending on context, Laban positioned himself sometimes as a supporter of the medium (as in the Film-Kurier), at other times as a vehement critic.[10] It was especially the Kulturfilm Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit [Ways to Strength and Beauty] (Germany 1925, Wilhelm Prager and Nicholas Kaufmann), which formed the important intermediary between dancers and the film sector. It portrayed the dance and body culture movement and brought numerous dancers (Niddy Impekoven, Mary Wigman) and contemporary dance schools before the camera. Scenes from the film show Laban with students of the Laban School of Hamburg in the dance drama Das Idol:

For many other dancers, these recordings were their first encounters with film production. For Laban, too, participation in Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit marked a decisive milestone. If, up to that point, he had retained a certain distance with regard to film as a «machine» that could record movement, by the end of the 1920s he became increasingly aware of cinema’s potential in the propagation of modern dance. By the end of the 1920s, film recordings of Laban and his students could be seen not only in Kulturfilms, but also in weekly newsreels—for example, the recordings of Tanz und Bewegungsübungen der Schule Rudolf v. Laban [Dance and Movement Exercises of the Rudolf v. Laban School], which was shown in 1928 as part of the Deulig-Weekly.[11] The film shows Laban’s students, who present the principles of his space and movement lessons with the aid of a life-size model of an icosahedron [a geometrical form] and perform a choral group dance (recorded in the garden of Laban’s school in Berlin-Grunewald). More than a documentary record of the dances, these recordings were choreographed specifically for the camera: the dancers’ glance penetratingly into the lens, which translates their backwards-seesawing movements into the depths of the space into (spatial, bodily and expressive) tension for the film spectator as well.

Excerpt from Monte Verità (FR 1997, Henry Colomer)

III. Modernizing Dance. A New Medium for a New Sensorium

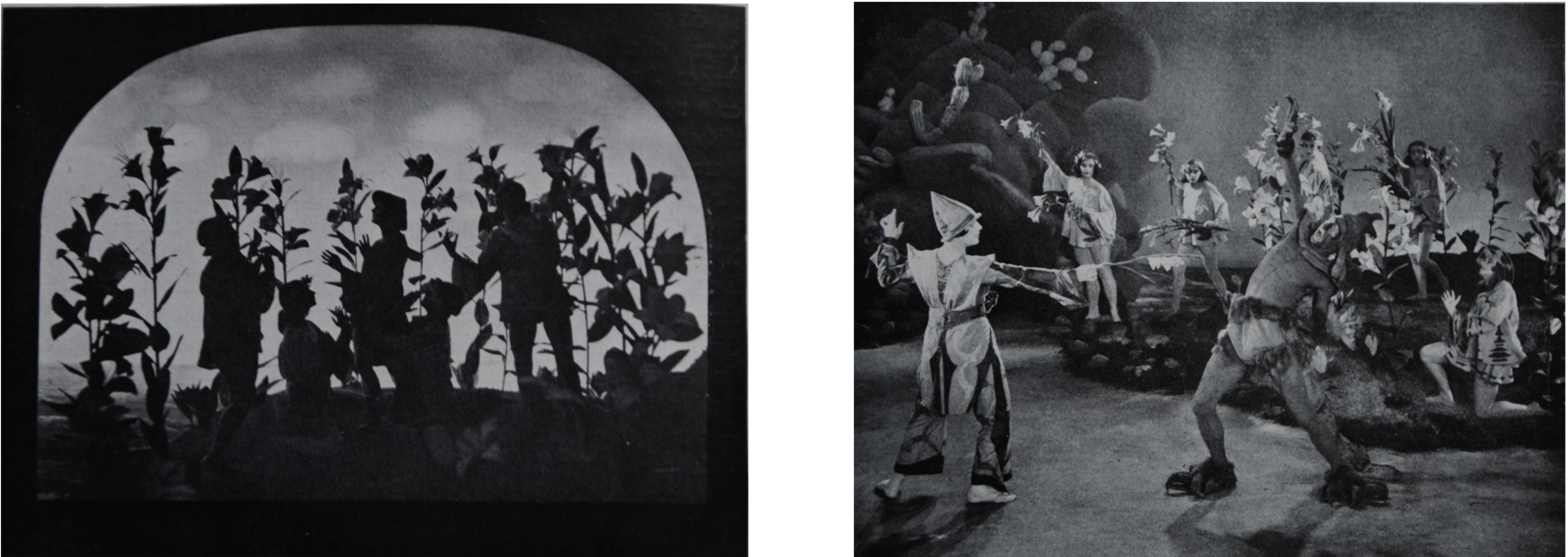

In his conversation with Lotte Eisner, Laban emphasizes that film is of interest to him not only as a form of movement notation, but also as a new technology. By referencing Der Drachentöter [The Dragon Slayer], Laban demonstrates that he had already taken up the possibilities of sound film as early as 1928. This was a “film-dance-pantomime,” which was recorded, under the direction of Laban and Prager, as “audible film” [“Hörfilm”] in 1927 or 1928 with a process developed by the company Bolten-Baeckers.[12] The film was based on the choreography Drachentöterei [Dragonslaying] by Dussia Bereska, which had premiered in 1923; dancing the main part, Laban appeared alongside the dancers in his troupe (the Laban Chamber Dancers [Kammertanzbühne Laban]). Der Drachentöter premiered in September 1928 at the technology exhibit of the Dresden Annual Expo—accordingly, it was considered first and foremost as a technical experiment with the new sound film process, and a refined “combination of technology and art.”[13] Laban himself also highlights the technical dimension, seeing in this film “proof that dance accompanied by music can be effectively adapted for sound film.”[14]

Stills from Der Drachentöter (Germany 1929), which Rudolf von Laban and Wilhelm Prager made first as a silent, and then as a sound film.

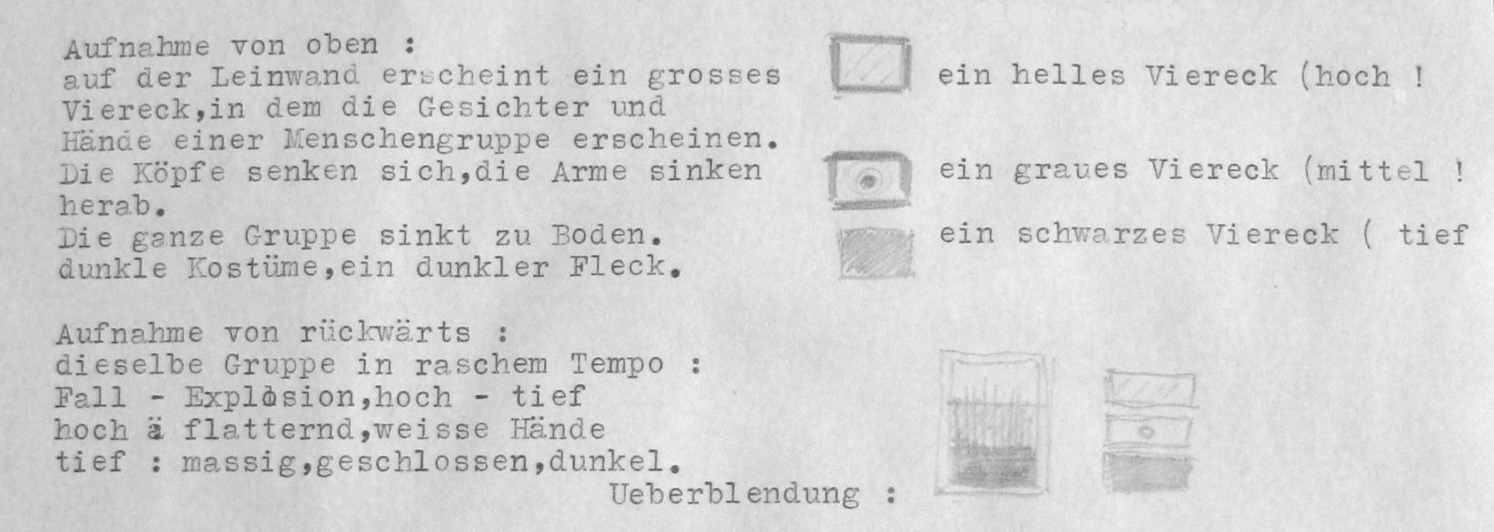

After the success of Wege zur Kraft und Schönheit [Ways to Strength and Beauty], Laban and the film director Wilhelm Prager began to compose a series of screenplays, among them the scenario for a “dance film” that would be “the greatest work of film-dance,” as Laban claimed in his conversation with Lotte Eisner. Indeed, sketches and scenarios for several dance films are to be found in the portion of his estate housed in the Leipzig Dance Archive.[15] With the project Das lebende Bild [The Living Image], for example, Laban intended to repurpose his notation system for a broader public. We can assume that this project—like many other film scripts that Laban completed toward the end of the 1920s—was never made. That said, Laban lacked neither conviction that film was an appropriate medium for the distribution of his dance and movement doctrine, nor the capacity to imagine how this might be concretely translated into film. From detailed illustrations in his film manuscripts, we can conclude that Laban had imagined a film language, which was intended as a sensory-perceptive overture to the viewer. By means of moving forms, surfaces and lines, recordings of “Footsteps in the Snow” in Das lebende Bild would gradually dissolve into animated forms of the notation system. Using double-exposure and other animation techniques, the notation symbols would be dramatized in such a way that the audience could understand the connection between writing and movement not only intellectually, but also through the dance itself. All the methods of composition that had been put to painstaking use in the screenplays and storyboards [Filmskizzen] aimed to foreground movement, in its associations, rhythmic correspondences and particular laws. Laban’s efforts to use the medium of film to address new forms of sensory-bodily experience bear a clear structural resemblance to the perceptual experiments that were contemporaneously undertaken by such filmmakers as Walter Ruttmann, Dziga Vertov, or Jean Epstein.[16] At the same time, Laban’s film projects, with their romantic imagery (mostly scenes of an idyllic nature untouched by civilization) stood in sharp contrast to avantgardistic concepts of the mechanized modernity.

Detail from Laban’s screenplay for the dance film The Living Image (ca. 1928). Source: UB Leipzig-Sondersammlungen/Tanzarchiv, Rep.028 III 3. Nr. 3.

Laban’s film theory appealed less to “film” as such, than to a multiplicity of diverse practices of film and cinema. He was not interested in elaborating a concept of a self-identical medium, as sought especially by classical film theory; rather, he ‘grasped’ (in a nearly literal sense of touch-experiment) the new medium as a multifaceted space of potentiality. Laban’s declared belief in film can be read not least as an attempt at ambitious self-promotion. His references to film allowed him to present himself in a broader sense as a “modern” dancer—namely, as an artist who employs “modern” technologies like film.

—Translated by Alex B. Bush

Download this article as a PDF.

Kristina Köhler is a post-doc researcher at the Department for Film Studies at the University of Zurich. She completed her PhD in 2016 with the dissertation Der tänzerische Film. Frühe Filmkultur und moderner Tanz (Marburg: Schüren 2017), focusing on the relationship between early film cultures and modern dance. She is also co-editor of the journal Montage AV and has edited the journal’s issue on film and choreography (2/24/2015).

Please cite this article as:

Köhler, Kristina. “A Dancer on Film: Rudolf Laban’s ‘film theory’.” The Promise of Cinema. 01-01-2017. ./index.php/a-dancer-on-film// .

[1] These connections are explored by the authors in Moving Pictures/Moving Bodies: Dance in German Cinema 1895-1933, eds. Michael Cowan and Barbara Hales, special issue of Seminar: A Journal of Germanic Studies 46.3 (2010).

[2] Tannenbaum, Herbert: Problems of the Film Drama (1913–14). In: The Promise of Cinema. German Film Theory 1907-1933, eds. Anton Kaes, Nicholas W. Baer, Michael Cowan (Oakland: University of California Press 2016), pp. 192-195; Balázs, Béla: Early Film Theory. Visible Man and The Spirit of Film, ed. Erica Carter (Oxford: Berghahn 2010).

[3] Laban, Rudolf von. Die Welt des Tänzers. Fünf Gedankenreigen (Stuttgart: Verlag von Walter Seifert 1920).

[4] Eisner, Lotte: Film und Tanz gehören zusammen. Tänzerischer Nachwuchs. – Schrifttanz statt Gefühlstanz. – Tonfilm und Tanzschrift. – Wann kommt die große Film- Tanzpantomime? In: Film-Kurier 143, (16. June 1928), n.p. A reprint of the German version recently appeared in Montage AV 24,2 (2015); it can be accessed online. An English translation of the text appears under the title “Film and Dance Belong Together” in The Promise of Cinema. German Film Theory 1907-1933, eds. Anton Kaes, Nicholas W. Baer, Michael Cowan (Oakland: University of California Press 2016), pp. 139-140.

[5] The event in Essen was intended to reinforce these efforts and, along with the simultaneously occurring dance festival, was planned as a major event in cultural policy, receiving much attention in the national and international press. “Around 1200 dancers and friends of dance from 16 countries have come together,” Der Sturm reported from Essen in June 1928.

[6] The reader reads the progression of movement from bottom to top; movements are depicted from a bird’s-eye view. The dancer “runs” on the middle line, such that his body is divided into its right and left sides. The movements for right and left sides of the body are indicated to the right and left of the middle line, respectively.

[7] Notice from the German Society for Written Dance. In: Schrifttanz. Eine Vierteljahresschrift 1.1 (1928), pp. 16-18, p. 16. Laban himself used the notation system especially for the planning and execution of his mass choreography, which frequently involved a “movement chorus” of more than 100 dancers. In the 1940s, however, Laban’s notation system was also used in scientific contexts (cf. von Hermann, Hans Christian: Bewegungsschriften. Zum wissenschafts- und medienhistorischen Kontext der Kinetographie Rudolf von Labans um 1930. In: Tanz und Technologie. Auf dem Weg zu medialen Inszenierungen, eds. Söke Dinkla and Martina Leeker (Berlin: Alexander Verlag 2002), pp. 134-161.

[8] Schuftan, Werner: Bewegungsschrift. Neue Wege zum Filmmanuskript. In: Film-Magazin. Die Wochenzeitschrift der Filmfreunde 3, 42, (1929), n.p.

[9] In the 1910s, a controversial debate over the “Autorenfilm [author film]” was sparked in the Germanophone world. Against a “literarization” of cinema, authors like Heinz Ewers, Hermann Häfker and, somewhat later, Béla Balázs claimed that cinema should take reference from the tools proper to it (camera, motion, etc.) (cf. Diederichs, Helmut H.: Frühgeschichte deutscher Filmtheorie. Ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg. Postdoctoral thesis at the J.W. Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, online under http://www.gestaltung.hs-mannheim.de/designwiki/files/4672/diederichs_fruehgeschichte_filmtheorie.pdf [last accessed 10 November 2015], pp. 50-56.) These questions were also vehemently discussed in France in the 1920s, by advocates of cinéma pur [pure cinema]. “The error of Cinema is the screenplay,” declared Fernand Léger in 1925 (cf. Léger, Fernand: Peinture et cinema. In: Les Cahiers du Mois 16/17, (1925), pp. 107-108, p. 107.

[10] In the first pages of his autobiography, Laban describes film as a “stupid machine” and “canned dance,” and opines that cinema is not capable of comprehensively reproducing dance, cf. Laban, Rudolf von: Ein Leben für den Tanz. Errinerungen [1935]. (Bern/Stuttgart: Paul Haupt 1989), p. 11.

[11]The film recordings were shown in the Deulig-Weekly 35/1928. According to the censorship card, the inclusion was “requested by Rudolf von Laban, Berlin-Grunewald.” Thus it is not improbable that this film—as Susanne Franco writes—was produced by Laban himself and that he also used it for presentations and educational purposes. (cf. Franco, Susanne. Rudolf Laban’s Dance Film Projects. In: New German Dance Studies, eds. Susan A. Manning, Lucia Ruprecht (Urbana/Chicago/Springfield: University of Illinois Press 2012), pp. 63–78).

[12] The film is considered lost. Photographs that give an impression of décor, costume, and the pantomimic dance performance were printed in an issue of the magazine Die Schönheit [Beauty]. In the same article, the film is described as a “hearing film” [Hörfilm] and “film-dance-pantomime.” (Cf. Die Schönheit. Mit Bildern geschmückte Zeitschrift für Kunst und Leben 24.5 (1928), pp. 194-195.)

[13] Anon: Der tönende Film. Eine Bereicherung des schönen Lebens. In: Die Schönheit. Mit Bildern geschmückte Zeitschrift für Kunst und Leben 24.5, (1928), pp. 192-194, p. 194.

[14] Laban, Rudolf von: Tanz im Film. In: Die Schönheit. Mit Bildern geschmückte Zeitschrift für Kunst und Leben 24.5, (1928), pp. 192-194, p. 195.

[15] A comprehensive representation of Laban’s film projects can be found in Franco, Susanne: Rudolf Laban’s Dance Film Projects. In: New German Dance Studies, eds. Susan A. Manning and Lucia Ruprecht (Urbana/Chicago/Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2012), pp. 63-78; Dörr, Evelyn: Rudolf Laban’s Dance Films. In: The Laban Sourcebook, ed. Dick McCaw (New York: Routledge, 2011), pp. 167-174.

[16] I develop this argument further in Köhler, Kristina. Der tänzerische Film. Frühe Filmkultur und moderner Tanz. (Marburg: Schüren, 2017).